The Close Encounters in War Journal opens the call for submissions for the Issue n. 8 (2025)

Images of exuberant crowds gathering on VE Day and VJ Day from Piccadilly Circus in London to Times Square in New York City have long shaped collective memories of 1945 as the moment when evil totalitarian dictatorships were finally defeated. Thanks to the sacrifices of Allied soldiers and civilians in what has since become known as the “Good War” peace returned and democracy was re-established. It was all a marked difference to how the year had begun.

From the end of January 1945 onwards the discovery of Nazi extermination camps in Europe, most infamously at Auschwitz, exposed the full horror of the Holocaust. The U.S, British, and Soviet forces who liberated the camps found emaciated survivors, mass graves, gas chambers and laboratories for medical experiments on humans. In February, the Allied Strategic Bombing campaign against Germany reached its horrific crescendo when incendiary bombing killed tens of thousands in Dresden. And in eastern and central Europe civilians suffered enormously. It was estimated that on German territory alone some two million women and girls were raped. Many civilians decided to take their own lives to escape what they feared to be a more horrible fate.

Hitler’s suicide on 30th April and the fall of Berlin in early May heralded the German unconditional surrender. But in the Pacific Theatre the fighting continued. During the battle of Okinawa alone (April to June 1945) over 7,600 U.S. troops and some 42,000 civilians were killed in an operation intended to secure a base for what would likely be an even bloodier operation, the invasion of Japan itself. And here, too, Allied bombing exacted a destructive retribution on Imperial Japan: in Tokyo over 84,000 died in March as a consequence of firebombing, which left 16 square miles utterly destroyed. The two atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August – acts which remain controversial and much debated – likewise caused enormous death and devastation, but they also accelerated Japan’s surrender and the end of the hostilities globally.

Even as the final Allied victory approached, new challenges emerged. In February 1945, at Yalta in Crimea, the ”Big Three” – Roosevelt, Churchill and Stalin – outlined plans for the division of Germany, for the payment of reparations, and for Soviet participation in the war on the Pacific Front. And in July, the Potsdam conference saw the hardening of tensions among and between the Allies so that by 1946 the early outlines of what would become a Cold War between East and West had already started to emerge.

The monumental historiography generated by this conflict has reflected the political and cultural divisions between the belligerents and it has highlighted the troubled and divided memories that exist within participant nations. The earliest comprehensive histories of the Second World War emerged from the field of international relations, and they emphasize the political dimensions of the conflict with a strong focus on strategy and military concerns (e.g., Churchill 1948, Liddell Hart 1970, Calvocoressi and Wint 1972, Taylor 1961). Broader surveys surfaced in the 1980s and 1990s, which looked at themes such as life on the home front and the socio-economic dynamics of total mobilization, including cultural transformations (Keegan 1989, Willmott 1989, Kitchen 1990, Parker 1990, Ellis 1990). Today, scholars tend to integrate local and regional perspectives into overarching narratives (Knapp & Baldoli 2012, Bourque 2019). New sub-disciplines such as diplomatic history and the history of intelligence have helped shed light on some critical aspects such as the Soviet Union’s role in the Axis’ defeat (Beevor 1999, Overy 2012), whereas memory studies and oral history have helped look more closely at people’s experiences (Terkel 1984, Berger Gluck 1987, Summerfield 1998, Dodd 2023).

Issue n. 8 of the CEIWJ aims to investigate the close encounters that occurred in 1945 between war and peace, between civilians and combatants, between the personal and the political, and between past, present, and future. Dr Sam Edwards will join the editorial team as guest editor.

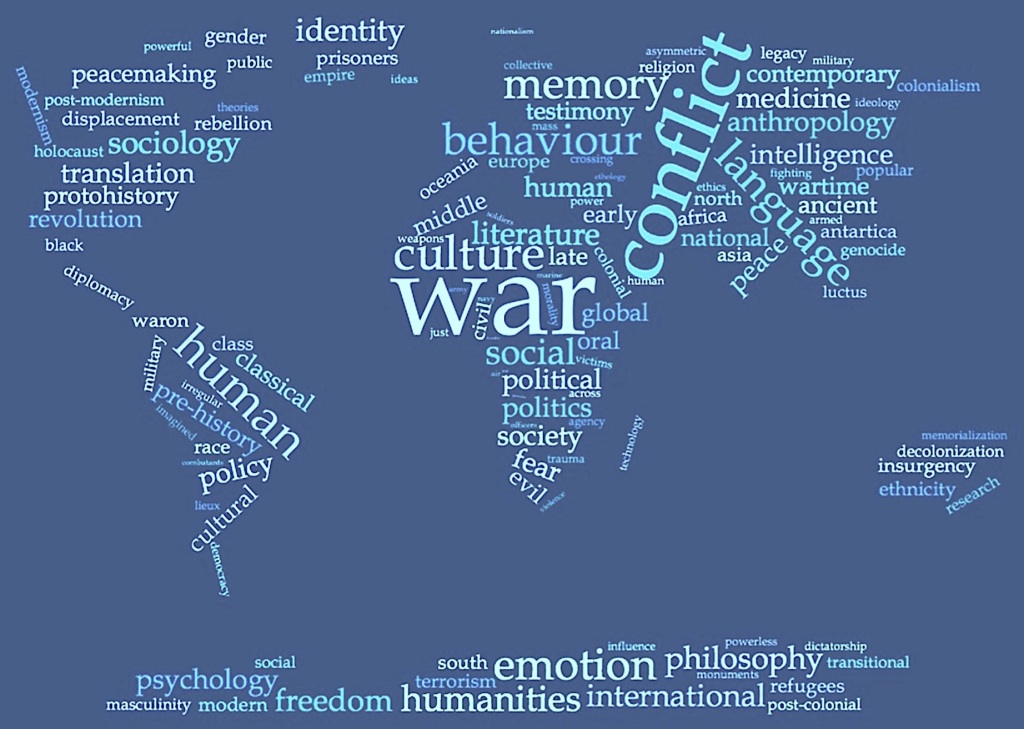

To do so, we invite the submission of articles focused on the investigation of 1945 from a broad spectrum of theoretical and critical perspectives in the fields of Comparative Literature, Cultural History, Ethics, Epistemology, Ethnology, Gender Studies, History of Art, History of Ideas, Linguistics, Memory Studies, Modern Languages, Oral History, Philosophy of Language, Postcolonial Studies, Psychology, Religion, Social Sciences, and Trauma Studies.

We invite, per the scientific purpose of the journal, contributions that focus on human dimensions and perspectives on this topic. The following aspects (among others) may be considered:

- Diplomatic encounters;

- Encounters between combatants from different belligerent countries;

- Encounters between civilians and combatants;

- Propaganda and ideology (e.g. political perspectives; racism; nationalism; religious fanaticism);

- Ethical and moral aspects (e.g. personal development; self-understanding; the relation with the others; justification of violence; acceptance of suffering and death);

- Anti-war attitudes (e.g. pacifism; criticism of violence; desertion and conscience objection; sabotage);

- Personal narratives and trauma;

- Decolonisation;

- Military occupation;

- Displacement and demobilisation;

- Identity and diversity (e.g. gender; ethnicity; cultural heritage);

CEIWJ encourages inter/multidisciplinary approaches and dialogue among different scientific fields to promote discussion and scholarly research. The blending of different approaches will be warmly welcomed. Contributions from established scholars, early-career researchers, doctoral students, and practitioners who have dealt with or used personal narratives in the course of their activities will be considered. Case studies that include different geographic areas and non-Western contexts are warmly welcome.

The editors of the Close Encounters in War Journal invite the submission of abstracts of 250 words in English by 31 March 2025 to ceiwj@nutorevelli.org. The authors invited to submit their works will be required to send articles of 8,000-10,000 words (endnotes included, bibliographical references not included in word count), in English by 1 June 2025. All articles will undergo a process of double-blind peer review. We will notify you of the results of the review in September 2025. Final versions of revised articles will be submitted in November 2025. Please see the submission guidelines at: https://closeencountersinwar.org/instruction-for-authors-submissions/.